The idea that has consumed Joe De Pinto’s life for the last four years sprang from a common frustration: When you’re at a popular bar, why does it have to be so tough to order a drink?

It’s a perfect question to ponder over a beer — which is just what De Pinto and his friend, Dan Wagner, did when they’d head to bars after playing minor-league baseball together in Birmingham, Ala.

When their playing days ended, they started taking serious steps to transform their idea — creating an app to make ordering drinks in bars easier — into a business.

Now, more than four years in, their app has slowly moved into 36 bars around the country. They have experienced the thrill of starting something new and seeing it take off.

Their growing company, Barpay, is making bars more efficient and earning bar owners and bartenders more money, while helping solve the original problem of waiting for drinks.

They’ve learned a lot, and even took advice from billionaire businessman Mark Cuban. But the road to success in any new business is an uneven path, and does not come without sacrifice.

De Pinto and Wagner put in long hours and sleep in RVs or on friends’ couches. They spend lots of time in bars but increasingly crave quiet nights at home.

They’ve put off personal relationships and marriages. They’ve foregone stable jobs and predictable salaries — all in pursuit of being their own bosses of a thriving tech startup.

America loves to celebrate entrepreneurs, visionaries who develop a novel idea and seize opportunity. What’s sometimes missing from the popular depiction, though, is the sheer amount of time and persistence needed in the journey from an idea to money-making business.

“We are trying to change an industry and how the places operate,” De Pinto says. “That’s not going to happen overnight. Maybe we were a little naïve at first, thinking this was going to be easier than it has been.”

The birth of an idea

The two met playing AA baseball for the Chicago White Sox organization in Birmingham. After games, like young players tend to do, they would go to a bar. Popular bars. Crowded bars.

They said to themselves: “Man, why is it a complete process to order a drink? There has to be something that technology can do about this.”

In early 2015, once their playing careers were finished, they drew up a business plan. Their idea was to create a smartphone app that lets bar patrons order drinks from their phones then pick them up at the bar.

By then, people were using phones to hail rides on Uber and order food on DoorDash and Grubhub — why not use an app to order drinks and avoid the crush of thirsty people at the bar?

They knew the perspective of customers. But what they needed was a broader view, a view from a bar owner.

They turned to a friend from De Pinto’s days as a student at the University of Southern California — who happened to own one of the best-known college bars in the country: The 901 Bar & Grill in Los Angeles, known as “the nine-o.”

“He told us, ‘You guys don’t know how big of an animal you’re about to try and tackle,’” De Pinto recalls. He told them it was insufficient to have a product that made ordering drinks easier for customers.

What they really needed to do was show bar owners that their system would be more profitable to use and easy to integrate into existing practices. If it were too costly or cumbersome, he told them, no bar owner would use it.

It was an important moment, and it made De Pinto and Wagner rethink their approach. They raised about $300,000 from friends and family, hired an app developer, and devised a strategy that would address the bar owner’s concerns.

They would make their system free to bars and would give them a printer to produce drink orders originating from customers’ smartphones. To make money, they would sell ads on the app — probably to beer and liquor companies.

Because bars wouldn’t be processing credit cards, they could sell more drinks. And that meant more tips for bartenders, too.

By the fall of 2016, Barpay was ready to launch. They started it at “the nine-o” near USC. They were living in an RV, parking it near the bar — where they hung out frequently and talked up the app to students — or at a nearby RV park.

The app was a hit with students and bar owners. They took it to Rocco’s Tavern, a bar near UCLA. They had 10,000 downloads in the first three or four months.

Tinder, the dating app, approached them and paid them a few thousand dollars to run a one-week campaign that advertised “swipe right rum-and-Cokes.” And Tinder liked the results. It was early, but it seemed promising.

They took their app to other bars near college campuses: University of California, Berkeley. UC Santa Barbara. UC Irvine. Arizona State. Everywhere they went, the app seemed popular.

But a problem arose: After going to a bar to promote Barpay, De Pinto and Wagner found the use of it would fade after they left. It was hard to keep the momentum up without continual promotion.

Schooled by Mark Cuban

To address that problem, De Pinto called on an expert. He looked online and found the email address of Mark Cuban, the owner of the Dallas Mavericks NBA team who is a businessman, investor and regular panelist on the entrepreneur show “Shark Tank.”

De Pinto sent Cuban an email describing his company’s dilemma — and to his surprise, Cuban replied.

In an email back-and-forth that lasted nearly a week, Cuban asked the two: Why aren’t you guys knocking on every door? Why aren’t you taking over all the bars on an entire street?

De Pinto replied that their young company had no marketing budget, no people on the ground.

“He told us, ‘Look, guys. Hustle is more important than a marketing budget. Everything else is just an excuse,’” De Pinto recalls. “We were like, ‘Damn! Mark Cuban just called us out!’”

The email exchange helped alter the company’s approach. Instead of focusing on individual college bars in different cities, they decided they needed to build a critical mass by targeting clusters of bars.

They decided to try Charlotte, N.C., near Dan’s hometown. It’s a growing, midsized city that has been attracting a lot of young professionals, and there is a high concentration of new bars in an area called South End, on the outskirts of downtown.

On a recent Saturday night in South End, De Pinto sipped an IPA at Sugar Creek Brewing Co. Outside, a young crowd sat at wooden tables while others played corn hole.

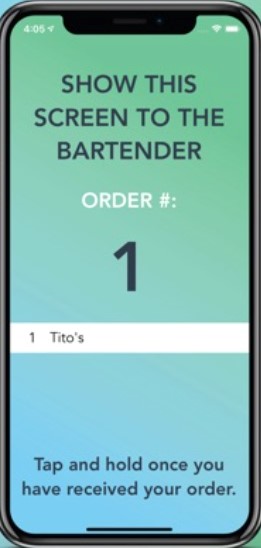

De Pinto demonstrated how it works: You go on the app, and after entering your credit card details, you pick a drink and send in the order. In a few minutes, it is ready behind the bar. You get your beer when you show the bartender the order on your phone. The tip is included.

On this night, the bar was not too crowded. Nobody else seemed to be using the app. Usage tends to pick up when there are a lot of people trying to get drinks. De Pinto says he’s not discouraged, and he’s learned not to expect overnight success.

He is heartened by listening to stories of other entrepreneurs on podcasts such as “How I Built This With Guy Raz.”

In one episode that resonated, for instance, the founders of Airbnb described how at first, nobody thought developing an app allowing users to stay in other people’s homes was a winning idea.

“It just takes time,” De Pinto says. “It takes a lot of boots on the ground.”

Stanley Ridgley, associate clinical professor of management at Drexel University’s LeBow College of Business in Philadelphia, says not everybody is cut out to start a business.

“Entrepreneurship is tough — don’t let anyone fool you,” he says. “Writing an idea on a napkin and waiting for the money to follow — that’s not how it works. It takes a relentless focus on the idea. The key is to not be discouraged by what people who don’t understand your vision are saying. You have to be the keeper of the vision.”

For De Pinto, persistence sounds like a lesson he’s learning — in addition to sales skills, marketing, strategy and technology. Now age 30, he’s seeing friends get married, have kids and buy houses. He’s postponed all that in pursuit of doing something big with Barpay.

“I’m not afraid to be on the streets if my big idea doesn’t work out, as long as we give this big idea everything we’ve got,” he says. “If we’re on the street playing a guitar for money, so be it. If we’re going to do this, we’re going to go all the way.”